Some of you may already know this, but underneath the love of Will Ferrell, the appreciation of a classy euphemism for genitals, the gratuitous use of the words motherfucker and c**t, is a girl who is incredibly snobby when it comes to film.

Yes, just as I don't really like fart jokes, I also am very pretentious when it comes to film. Do not get me started on the subject of why filmmakers should also be film critics. Or try to suggest that watching narrative cinema is a passive experience. I will crush you with film analysis. I will also talk for a very long time with little to no pauses.

As recent posts will suggest, I'm not so pretentious about film that I enjoy art cinema. That's for people who can't tell a story or be bothered hiring a crew that knows what they're doing. It's also for wankers who know nothing about film to discuss the power of the images. Yeah, all I see is Jurgen Haarbemaster and Vulva - helping all of us who prefer to explore film in an interesting way to take the piss about people who can't do it right.

Why, then, am I a film snob? Because I detest films that reveal nothing about either characters, genres or visual styles. I want to vomit at films made purely to generate revenue. I get irate when casting decisions are made purely on looks and not talent.

I like Ingmar Bergman films. In fact, I think he was one of the best filmmakers of all time. I could, hypothetically, talk about why Citizen Kane is so amazing, or why Alfred Hitchcock's films are perfect for several days. I love Jean-Luc Godard and I think Robert Altman is still the master of ensemble dramas. I also think Romero is the zombie film's real father, if not its biological father. I can find subtext in many films people consider to be ridiculous, shallow, or just plain disgusting, like Wes Craven's Last House on the Left. Which is all three, in equal measure.

But more than that, the films I admire and the films I want to make are so ridiculously wanky in scope, that sometimes I astound even myself. I want to reach that perfect combination that filmmakers like Scorsese, Tarantino, Wright, and Coppola have done before me: that perfect blending of style and substance - an exploration of film that doesn't feel shallow, using characters so perfectly that you like them or are fascinated by them even if they are merely a device or yet another exploration of film.

I want to explore the work of other filmmakers and develop my style from them. I want to make analyses of genre so powerful that they inspire a hundred nerdy blog posts like this one. I want to hear lines of my dialogue quoted on the streets and in the statuses of social networking profiles. I want a visual style that people literally wee themselves over, they're so impressed.

I began this quest with the first film I actually wrote, or came up with the concept for. It was a music video for a friend's band. It was supposed to be an homage to those wonderfully bad B-Movies with monsters in them, using ridiculously poor effects. Check out my earlier post on it - Sirens by Fictions, formerly Montana Fire. Whether it was through poor shot choice or whatever, it didn't work. So what we did instead was intercut the band fleeing from a monster with scenes from the 1958 sci-fi classic The Day The Earth Stood Still. What started as pure homage and an exploration of old filming techniques became an exercise in montage, really. An ability to create meaning between two disparate sets of images. And still, in essence, an homage to old films that didn't have the same kind of technology we do.

The next film was another exploration of genre and the conventions of the buddy-cop drama, much in the vein of Hot Fuzz. However, I wanted to put a twist on it by changing the location of the drama for comic effect: the two cops became dishpigs, and the police station became a small restaurant. It was designed to be a sort of origins story that would form the basis of a television series or feature film, however, again, being student filmmakers and therefore still pretty rubbish, the film had to be modified quite a bit from its original form. The bad lighting couldn't really be saved with colour correction in post, so it became a black and white film. The audio issues couldn't be fixed without a lot more time, either, so it became a silent film. Not just any old silent film, either: a 1980s silent film. I'm pretty sure it's the only one of its kind. While again, my aim was still present - to do an analysis of genre, it's not quite what I had in mind, though people were quite blown away with it, although sadly not the tutors.

Well, that changed with the film I made recently. While on my student exchange, I decided I wanted to direct a film to see if I could do what I had wanted to do for quite some time. And the film I had to make was a film with a non-linear narrative. That was the part that was the most exciting. So when I first started thinking about it, this is what I wanted to do:

Make an art film that was not actually an art film, but a series of randomly assembled homages to scenes in films that sort of relied on an artistic feel - surrealism and all that sort of thing. The techniques some early filmmakers were going to be played with, too. So the scenes I wanted to rip off were the following:

The in-camera editing style of Melies

The organisation of time in Un Chien Andalou

The dream sequence in Carrie

The end of Blow-Up

Good, right? Yeah. The film changed but the pretentious ambition I always had for it never changed. The original story goes something like this: a couple are on a way to a party. They're trying to take a shortcut suggested to them by a friend of the guy. They get lost in these eerie, surreal woods and strange things start to happen. They become angry with each other and the guy leaves the girl. While they're separated, he stumbles across something sort of awful, but while looking for her he trips and bangs his head, knocking him unconscious. The girl looks for him all night and finds him unconscious, thinking he's dead. He wakes up, and in his groggy state he tries to lead her to what he found, with her help. And what is it that he's discovered? They're in a children's playground. They've been lost in a playground the entire time. To top things off, a little girl is playing and she was been playing with them while they've been lost, taking their things and giving them gifts.

The way it would play out is that it would start with the couple fighting, then cut to the girl by herself, staring at something offscreen. We'd then cut to them at night, trying to work together. Then back to day time, and they've found an old tape recorder. Upon discovering that it works, they dance to the music. Then back to the girl, only this time we would see a little more and also we would see the little girl staring back at her. Then slight tension between the couple during the day when they are trying to find their way. Then we would return to the fight at the beginning and see the guy walk off. From here, the film would be linear but still surreal - we'd then cut to the girl looking for the guy and discovering him, then discovering the playground. Then, the little girl would begin playing a game of imaginary tennis and the girl would join in.

Oh, wanna know the best part? The film is called La Cour. Which in French is...playground. See what I did there?

Structurally, the finished film is still the same, minus the dancing scene (we didn't have time, shame), however, we shot in such a way as to make it even more confusing than I intended. Basically, the film goes like this: we start with the couple fighting. We then cut straight to the girl. Then, we cut to them walking together at night. Then the title. Then, the slight tension on the bridge during the day, followed by the repeated scene of the girl staring at something, followed by a little girl. It's now obvious that they're in a playground. Then, we cut back to the fight again, repeated but not quite as long. Then we see the girl searching for her boyfriend and finds him. It's no longer clear what's happened to him. Then we cut to them reaching the playground. The girl helps her boyfriend sit down and, seeing the little girl, throws the imaginary ball to the little girl for a while.

It's incredibly confusing, but now I say it's supposed to be. And it is - through shooting the film it became more about this couple in this odd, surreal wood setting. The playground at the end makes it a little more hopeful than absurd and ridiculous and I wanted the structure to sort of suggest the state of mind of the characters. Now it could even resemble the girl's memories of that time in her life.

I'd now like to share with you some of what I wrote for my tutors when handing in the film:

What sources influenced your practice in this work? This must include works by filmmakers and/or artists, but could also include works of fiction/poetry; theory; newspaper articles; music; dreams or conversations (for example.)

When I first researched this unit of the course in Australia, I originally conceived of an artists' moving image film, and I wanted to use this film to explore the relationship between art cinema and narrative cinema. The film would be, in essence, an homage to surrealist film techniques and the more abstract moments in some of my favourite films, including Un Chien Andalou (Bunuel and Dali, 1928), especially the quote from Bunuel about the film: “No idea or image that might lend itself to a rational explanation of any kind would be accepted.” My rather lofty and perhaps pretentious ambition was to create a film that rejected all atempts to find meaning within it, using images from narrative films.

I then decided to develop a narrative and was inspired by an episode of The Twilight Zone called 'Strange Planet.' In the episode, three astronauts crash-land on another planet, and without resources or a way home, tension begins to mount between them. One walks away and the others look for him. As they search, they find a symbol drawn in the sands. When they find him he is near death and before he can explain the symbol he does in fact die. As they continue searching the landscape, they make a horrific discovery: the symbol was supposed to represent power lines. They have been on Earth the entire time.

The films I wanted to pay tribute to were the following:

Badlands (Terence Malick, 1973) - the scene in which the young lovers escape to the woods and dance to the song 'Love Is Strange'. I really liked this part of the film, because it represents a slightly surreal and almost absurd moment between the characters. I wrote a scene as an homage to this scene both to heighten the more absurd elements of the story, and to provide light relief in the mounting tension between the two characters.

Carrie (Brian DePalma, 1976) - Susan's dream, in which she visits Carrie's grave – it was shot backwards and reversed in the editing process and I wanted to employ this technique, as I was still interested in experimenting with different ways of filming to create a surreal effect. Within my script for La Cour, the moment in which one of my protagonists, Laurie, is literally separated from her boyfriend Cabe, it is at a point when she is most affected by the landscape – she has been searching for him all the night and she is numb with cold and fear. I wanted to reflect this visually through the shots and also the editing.

Blow-Up (Michaelangelo Antonioni, 1966) - the end of the film, in which David Hemmings' character revisits the park in which he captured a murder on camera. The mystery is never resolved; when he gets to the park, a group of mimes play imaginary tennis, and for a moment he plays along. The film is about a photographer who witnesses a strange event in a park, and the unassuming park becomes a dangerous other realm through the lens of his camera. He believes this evidence he has captured will change his life, but it changes nothing – he is still witnessing other people through a lens. After his experience and a night of hell looking for the woman who may know more about the murder, he returns to the park only to find the mimes who had disrupted social order in the street earlier in the film have disrupted the order of the park. At this point, the absurdity of his situation seems to hit him and he has nothing to do but to play along with the absurdity. I wanted to recreate this as the ending of my film, as I felt the story echoed this element of Antonioni's film (yes, I am actually comparing myself to Antonioni. How uncomfortable), the characters going through a night of hell only to be presented with an absurd and almost meaningless resolution. The horror of realising they had been in a park all along would give way, especially for Laurie, to a sense that she could do nothing now but to play along with the game she and Cabe had been unwittingly been involved in all along.

I was also inspired by the structure of the novel Catch-22, in which the structure of the novel reflects the memories of the main character, and one incident that forms the end of the novel is constantly referred to throughout the book, using one particular image.

During preproduction, and after consultations with Joe and discussing the look of the film with Sioned, I also looked to the television series Peep Show, which is shot entirely using subjective pov of characters within the show. This was to play up the element of the characters being watched and played with. This was because Joe suggested that the idea of who is playing a game with the characters could be clearer, and Sioned and I decided on shooting the film in the style of Peep Show, in that every shot in the film would be the subjective pov of one of the characters. Much of the shots we had using the tripod were designed to reflect the pov of the small girl we see in the playground at the end of the film. What I was suggesting most of all is that as the writer and director it was me playing the game not so much with the characters but with the audience, however, I'm not skilled enough as a writer or director just yet to make that as clear as I maybe could have.

Wednesday, December 16, 2009

Monday, December 7, 2009

Nearer, Father, Nearer

I'm currently writing an essay on art cinema and its representation of the body, gender, and identification. Ha. To me, the essay question is, in the words of Cher Horowitz, 'simply a jumping-off point to start negotiations.' Par exemple, take the essay I was supposed to write for the atrocious joke of a compulsory course, International Media Studies. I don't know how many of you out there are aware of this, but the discipline of Communication Studies is a vile pit of horror and despair. In order to avoid this, I would happily drink wasps, stab my eyes out with lit sparklers, and go on an over-60s singles cruise. But I digress. International Media Studies. I can't really remember the essay question - it was something about discussing theories of the way in which communication is enabled across countries or something yawn-worthy like that. Contraflow was in there somehow. It was supposed to be a 'research essay', in which you merely researched these boring theories and made some irrelevant comment on the way in which they applied to international media relations. I'm almost positive that essay would be laughed out of a HSC curriculum for being too simple.

So in the opening paragraph, I outlined exactly why this question and approach to the study of international media relations was tired and crap, and discussed Foucault's concept of power and how these power relations were enacted via the media - this constant back-and-forth between media outlets. I have no idea if this impressed any of my tutors (especially as one of them was ridiculous - she accused an entire class of plagiarism for using a modern version of the Harvard Referencing System - idiot), however, since I received a decent grade considering I failed an assignment due to my sheer refusal to stick to the assignment guidelines, I can only assumed one of them at least valued my articulately and well-written opinion of their ridiculous course.

And now I come to my current essay. Call me a slave to narrative cinema, but upon taking a course that focuses on the development of art cinema, I can now say with conviction that I hate art cinema with a passion reserved only for paedophiles, racists and homophobes. Ok, so maybe I don't hate them that much. I guess what I hate is that anything with a story is immediately dismissed as brainwashing rubbish enslaving a passive audience and a naked dude rubbing tomato sauce on his penis is considered a masterpiece. I'm almost positive this 'art film' has been recreated on many drunken football tours and buck's nights.

Many art films investigating the same thematic concerns as horror films have been automatically placed in a higher cultural category for far too long. For example, Stan Brakhage explores the demise of the human body in several films and while these are difficult to access, they are still praised for their contemplation of human frailty and ask the spectator to respond to the sight of the body in decay. So do horror films. Simply because a lot of them appear to be an excuse to show ample bosoms and graphic violence, they reveal what is usually unseen - death and the body's destruction. The unseen fascinates us, the unknown pulls us toward it and death is one of these things. Most of us don't know what our insides look like, so why not take a peak in the safety of the cinema or our own homes?

Zombie films contain the same themes of death and the contemplation of the body's destruction. Simon Pegg, my dream man, argues that slow-moving zombies are a metaphor for death, slow, yet sudden, always inevitable. Yet these are considered a lower form of cinema.

Artists who work in film always suggest that the experience of watching a narrative film is too passive, and their work challenges the spectator to be more active. Well, first of all, fuck you. The act of watching a film is never passive. They assume that simply because sitting in a room focusing your attention on a single space for a prolonged period of time is passive. It's an illusion. If watching a film was truly passive the images in front of us would not make any sense. Our brains and eyes are constantly assembling the footage we're given, and many films demand a physical and emotional response from us as well, such as horror, melodrama and, ahem, porn.

Many horror films privilege bodily sensation over narrative, and thereby form an alternative to narrative cinema. Sound familiar? Yeah, art film wankers say the same thing, only because a person decides it should be in a gallery it's better than a film about a guy cutting up teenagers with a chainsaw, or a film about the undead chowing down on human flesh like it's a tasty bucket of chicken.

After viewing many of these ridiculous films (and skipping more than the odd class out of sheer frustration), I have decided that the only value they have held is that now I know better how to make fun of them in my own narrative films. So how am I going to answer the essay question mentioned in the first line of this post? Well, essentially, I am going to suggest in an articulate and well-written prose style that art cinema and horror do the same shit, only horror does it better. Who knows, perhaps this may be my conclusion:

Art films are pretentious shit and horror films such as Wes Craven's Last House on the Left fucking rule.

So in the opening paragraph, I outlined exactly why this question and approach to the study of international media relations was tired and crap, and discussed Foucault's concept of power and how these power relations were enacted via the media - this constant back-and-forth between media outlets. I have no idea if this impressed any of my tutors (especially as one of them was ridiculous - she accused an entire class of plagiarism for using a modern version of the Harvard Referencing System - idiot), however, since I received a decent grade considering I failed an assignment due to my sheer refusal to stick to the assignment guidelines, I can only assumed one of them at least valued my articulately and well-written opinion of their ridiculous course.

And now I come to my current essay. Call me a slave to narrative cinema, but upon taking a course that focuses on the development of art cinema, I can now say with conviction that I hate art cinema with a passion reserved only for paedophiles, racists and homophobes. Ok, so maybe I don't hate them that much. I guess what I hate is that anything with a story is immediately dismissed as brainwashing rubbish enslaving a passive audience and a naked dude rubbing tomato sauce on his penis is considered a masterpiece. I'm almost positive this 'art film' has been recreated on many drunken football tours and buck's nights.

Many art films investigating the same thematic concerns as horror films have been automatically placed in a higher cultural category for far too long. For example, Stan Brakhage explores the demise of the human body in several films and while these are difficult to access, they are still praised for their contemplation of human frailty and ask the spectator to respond to the sight of the body in decay. So do horror films. Simply because a lot of them appear to be an excuse to show ample bosoms and graphic violence, they reveal what is usually unseen - death and the body's destruction. The unseen fascinates us, the unknown pulls us toward it and death is one of these things. Most of us don't know what our insides look like, so why not take a peak in the safety of the cinema or our own homes?

Zombie films contain the same themes of death and the contemplation of the body's destruction. Simon Pegg, my dream man, argues that slow-moving zombies are a metaphor for death, slow, yet sudden, always inevitable. Yet these are considered a lower form of cinema.

Artists who work in film always suggest that the experience of watching a narrative film is too passive, and their work challenges the spectator to be more active. Well, first of all, fuck you. The act of watching a film is never passive. They assume that simply because sitting in a room focusing your attention on a single space for a prolonged period of time is passive. It's an illusion. If watching a film was truly passive the images in front of us would not make any sense. Our brains and eyes are constantly assembling the footage we're given, and many films demand a physical and emotional response from us as well, such as horror, melodrama and, ahem, porn.

Many horror films privilege bodily sensation over narrative, and thereby form an alternative to narrative cinema. Sound familiar? Yeah, art film wankers say the same thing, only because a person decides it should be in a gallery it's better than a film about a guy cutting up teenagers with a chainsaw, or a film about the undead chowing down on human flesh like it's a tasty bucket of chicken.

After viewing many of these ridiculous films (and skipping more than the odd class out of sheer frustration), I have decided that the only value they have held is that now I know better how to make fun of them in my own narrative films. So how am I going to answer the essay question mentioned in the first line of this post? Well, essentially, I am going to suggest in an articulate and well-written prose style that art cinema and horror do the same shit, only horror does it better. Who knows, perhaps this may be my conclusion:

Art films are pretentious shit and horror films such as Wes Craven's Last House on the Left fucking rule.

Labels:

art cinema,

body,

horror,

representation,

spectatorship

Thursday, October 8, 2009

The 'Eye' in Film

A friend remarked on her Facebook status that she thinks she's destined to watch Un Chien Andalou and Meshes of the Afternoon at least once a year for the rest of her life. I feel as though I'm destined to listen to idiots talk about those two films at least once a year for the rest of my life.

I love Un Chien Andalou. I think it's so brilliant, and I think it's because the filmmakers (surrealist artists Salvador Dali and Luis Bunuel) have used conventional Hollywood narrative structure and applied it to a 'meaningless' set of images. My dear, dear friend Tori visited the Dali exhibit in Melbourne and found me a quote from Dali about the film, and though I can't remember it verbatim, it was roughly that the film was a deliberate attempt to subvert meaning, the images were put together in order so as to be completely meaningless.

While this is an interesting aim, it will never work. Film, much like all other art, cannot be meaningless. My old friend (I have a lot of friends, don't I?) Roland Barthes, whom I like to call Barty, hits the nail on the head in Death of the Author when he says that the death of the author means the birth of the reader. Meaning is instantly created whenever an artwork is received. As soon as someone looks at an artwork, they cannot help but create meaning for themselves.

I have watched Un Chien Andalou in three film courses; Genre Studies: The Horror Film, Screen Culture, and now Alternative Histories of Film and Video. The last two consider the film to be an art film, part of the surrealist movement's attempt to subvert meaning and narrative structure. But the first viewing hinted at a meaning beyond that.

The most memorable moment in this film is in the opening sequence. A barber (played by Bunuel), sharpens his razor and disturbed, he looks out at the night sky, and we see a full moon. He goes back inside and holds a woman's face in place. Then holds her eyes open. She doesn't struggle. I think you know what's about to happen.

We cut to a shot of the moon being slashed by a cloud, and we think this is the symbol for the woman's eye and the barber's razor. Nup. Merely a break - we cut back to the razor slicing the woman's eye open.

When I watched this in the horror course, people actually cried out in, well, horror, as it happens. People who laughed at me when I said the Blair Witch Project was truly scary because of the absence of a monster, while these hipsters all said the same film (The Omen. Pft!). I, meanwhile, did not cry out. I was fascinated. I hadn't seen anything like it before. And the fact that for all intents and purposes, it was real (Bunuel slices the eye of a dead sheep - not a lady), made it even more extraordinary, that a film made so long ago had the power to make people squirm.

In the seminar on Tuesday night, for Alternative Histories of Film and Video, we discussed how and why these 'old' art films may still have the power to shock people. We hinted at why, but never really talked about it in any great detail. And it's so important! We talk about it alllll the time in film and yet all we could say about it is that it's a fragile part of the body and we don't like seeing it damaged.

It's all about the eyes, my friend. In horror, the image of seeing an eye destroyed is pretty common. Bits of the body being cut up in general, in fact. So much of horror deals with the body - the uncanny (something familiar becoming unfamiliar and the ensuing sensation that produces), the abject (seeing parts of ourself that disgust us), and the unseen elements of death becoming seen) are all associated with images of the body destroyed in horror. So on one level, horror is shocking because we are shown exactly how fragile the body is and how it can be torn apart. So, yes, the people in my class that raised this point are quite correct.

But I think in the case of the eye, it's more complicated than that. Another tutor reminded us last week that we are a predominantly visual culture, that is, we watch more television and cinema than we read books. Screen Culture discussed the idea that we are constantly engaging with the world through a screen. The eye is the primary way we process information. Seeing it shut down makes us feel vulnerable because having our eye damaged, whether through illness, childhood accidents, altercations with Uma Thurman, or by having it sliced open, would mean that we would instantly lose our way of processing information.

We lose our way of identifying with characters. The camera is often referred to as the eye. In many horror films our eyes are restricted to the eyes of a killer, but rather than identifying with them we feel disoriented because their vision is often obscured. In narrative films in general, however, we are encouraged to see the camera as the eye, allowing us to view other people in a new way, and without guilt, it's been suggested.

Hmm, why is that more complicated than seeing our fragile little peepers torn apart? Because it's our worst nightmare. Of course, being blind is not the end of things. Radio programs prove that we cannot process information and create meaning without using our eyes. However, it's the eye that is possibly the body part used the most in processing information and seeing our worst fears realised on film is shocking. And it will always be shocking.

I love Un Chien Andalou. I think it's so brilliant, and I think it's because the filmmakers (surrealist artists Salvador Dali and Luis Bunuel) have used conventional Hollywood narrative structure and applied it to a 'meaningless' set of images. My dear, dear friend Tori visited the Dali exhibit in Melbourne and found me a quote from Dali about the film, and though I can't remember it verbatim, it was roughly that the film was a deliberate attempt to subvert meaning, the images were put together in order so as to be completely meaningless.

While this is an interesting aim, it will never work. Film, much like all other art, cannot be meaningless. My old friend (I have a lot of friends, don't I?) Roland Barthes, whom I like to call Barty, hits the nail on the head in Death of the Author when he says that the death of the author means the birth of the reader. Meaning is instantly created whenever an artwork is received. As soon as someone looks at an artwork, they cannot help but create meaning for themselves.

I have watched Un Chien Andalou in three film courses; Genre Studies: The Horror Film, Screen Culture, and now Alternative Histories of Film and Video. The last two consider the film to be an art film, part of the surrealist movement's attempt to subvert meaning and narrative structure. But the first viewing hinted at a meaning beyond that.

The most memorable moment in this film is in the opening sequence. A barber (played by Bunuel), sharpens his razor and disturbed, he looks out at the night sky, and we see a full moon. He goes back inside and holds a woman's face in place. Then holds her eyes open. She doesn't struggle. I think you know what's about to happen.

We cut to a shot of the moon being slashed by a cloud, and we think this is the symbol for the woman's eye and the barber's razor. Nup. Merely a break - we cut back to the razor slicing the woman's eye open.

When I watched this in the horror course, people actually cried out in, well, horror, as it happens. People who laughed at me when I said the Blair Witch Project was truly scary because of the absence of a monster, while these hipsters all said the same film (The Omen. Pft!). I, meanwhile, did not cry out. I was fascinated. I hadn't seen anything like it before. And the fact that for all intents and purposes, it was real (Bunuel slices the eye of a dead sheep - not a lady), made it even more extraordinary, that a film made so long ago had the power to make people squirm.

In the seminar on Tuesday night, for Alternative Histories of Film and Video, we discussed how and why these 'old' art films may still have the power to shock people. We hinted at why, but never really talked about it in any great detail. And it's so important! We talk about it alllll the time in film and yet all we could say about it is that it's a fragile part of the body and we don't like seeing it damaged.

It's all about the eyes, my friend. In horror, the image of seeing an eye destroyed is pretty common. Bits of the body being cut up in general, in fact. So much of horror deals with the body - the uncanny (something familiar becoming unfamiliar and the ensuing sensation that produces), the abject (seeing parts of ourself that disgust us), and the unseen elements of death becoming seen) are all associated with images of the body destroyed in horror. So on one level, horror is shocking because we are shown exactly how fragile the body is and how it can be torn apart. So, yes, the people in my class that raised this point are quite correct.

But I think in the case of the eye, it's more complicated than that. Another tutor reminded us last week that we are a predominantly visual culture, that is, we watch more television and cinema than we read books. Screen Culture discussed the idea that we are constantly engaging with the world through a screen. The eye is the primary way we process information. Seeing it shut down makes us feel vulnerable because having our eye damaged, whether through illness, childhood accidents, altercations with Uma Thurman, or by having it sliced open, would mean that we would instantly lose our way of processing information.

We lose our way of identifying with characters. The camera is often referred to as the eye. In many horror films our eyes are restricted to the eyes of a killer, but rather than identifying with them we feel disoriented because their vision is often obscured. In narrative films in general, however, we are encouraged to see the camera as the eye, allowing us to view other people in a new way, and without guilt, it's been suggested.

Hmm, why is that more complicated than seeing our fragile little peepers torn apart? Because it's our worst nightmare. Of course, being blind is not the end of things. Radio programs prove that we cannot process information and create meaning without using our eyes. However, it's the eye that is possibly the body part used the most in processing information and seeing our worst fears realised on film is shocking. And it will always be shocking.

Labels:

bunuel,

dali,

eye,

horror,

kill bill,

surrealism,

un chien andalou

Monday, September 28, 2009

The Picture paints a bad adaptation: Dorian Gray

When you love a book so much it changes your life, you should never think that the film adaptation will ever be as good. I've used this rule with the original version of The Picture of Dorian Gray. I wish I'd known better with this new British crack at Oscar Wilde's incendiary yet sole novel.

Whenever I read The Picture of Dorian Gray, which is often, I am amazed at the way this study of morality is so timeless and remains relevant even today. I've secretly wanted to adapt this book properly (see previous blog entries for more), and I thought perhaps I'd lost my chance when I read in Interview that Benjamin Barnes was playing Dorian Gray. Yeah...still have a chance to do it right.

Because the novel is really about the soul. Does it exist? What if we could see the ways in which we corrupt our soul? Would we use it as a constant reminder to be morally good, or would we use it to be bear the burden of all our misdeeds? It's also about society's obssession with youth, and what we would forego to recapture our youth. As Harry says, the only way to recapture your youth is to remember all the mistakes you made, and make them over again.

Which, by the way, is one of the very few lines of dialogue from the novel that feature in the film. I cannot believe the extent to which this film ignores the themes and concerns of the novel. All references to morality, pleasure and the soul are skipped over, so insubstantial that you feel they were put in as a break from all the sex scenes.

There are changes to the novel that make the film's plot and story seem weak. Sybil Vane's dramatic appearances are nonexistent, and therefore so is the reason for her suicide. And any credible reason for Dorian's dismissal of her. Dorian and Lord Henry, or Harry, become very superficial characters, praising only art, and pursue beauty at all costs, Dorian more so than Harry. And yet the writer has ignored this for the most part. The conversation that leads to Dorian's wish that Basil's portrait of him age is almost entirely superficial, but for the wrong reasons. Sure, there are a lot of conversations in the novel that would be hard to translate into film, but the dialogue has been paraphrased to the point of meaninglessness.

In the plot, essentially, Dorian meets Basil, who paints a portrait of him. He meets Harry, who takes him to a seedy bar and tells him to drink up. Dorian decides this is a good idea and gives his soul for eternal youth. The portrait begins to age and bear all the scars of his sexual conquests. He kills Basil after showing him the portrait, then buggers off for 25 years. Harry has a daughter, who Dorian falls in love with, Harry discovers his secret and tries to kill him. Then Dorian decides to let himself be destroyed with the picture after Harry's daughter Emily tries to save him. Dorian destroyed, the portrait reverts back to its former glory. Harry keeps it.

It seems like the novel, but it's so disgustingly superficial. The characters, the visual style, the narrative, and that's what it should be! Because describing in detailed paragraphs why the film is such a poor adaptation would take way too long, I'm going to list them here:

1. Dorian is a brunette. In the novel, he looks young, barely 20, and angelic, with curly golden hair and bright blue eyes. He looks like an innocent babe, which makes his eternal youth seem like a blessing. It also saves him from being completely ostracised from society. When people see his young face and angelic looks, they can't believe the stories are true. Ben Barnes is gorgeous, don't get me wrong, but he always looks dangerous and saucy. You never believe in his innocence, even when he really is.

2. Sybil knows Dorian's name. She only ever knows his first name in the novel, and calls him Prine Charming. One of Dorian's former conquests knows this and refers to him so at the opium den, which leads James Vane to find him. In the novel, Dorian's engagement to Sybil is known only to Sybil and her family, Basil and Harry. Dorian fears his involvement with her death and Harry assures him that no one will ever know. Which makes it more shocking later when his past catches up with him in the form of James Vane trying to kill him.

3. Dorian's pleasure in art is absent. Which changes his relationship with Sybil, making it little more than a plot device. Dorian's treatment of her is truly cruel, the first time we see what he is capable of now his soul is separate from him, and Lord Henry's influence is almost total. His preference for art over some life is what makes both he and Harry more monstrous, and the breakdown of his and Sybil's relationship looks foolish, making her suicide foolish. Sybil is essentially an actress. All she knows is the theatre, and the only things she knows about romance she learned from Shakespeare. It is this investment in drama that attracts Dorian, and when she discovers reality, it repels him. So her final desperate act is her return to drama. It is diminished in the film, especially as it is Sybil who dismisses Dorian, not the other way around.

4. Harry seems intentionally malicious at points. Though Harry is shallow and cruel, his corruption of Dorian is never a serious attempt to ruin the boy. He sees a blank canvas. Just as Basil is inspired by Dorian's physical beauty, Harry is inspired by Dorian's naivety. He sees someone he can model after himself, someone not as bound to societal rules as he is, being married and held in high regard by his family. He's also bored with his society and with Basil. He's not as cruel as he seems in the first half of the film. I never thought Colin Firth would make a good Lord Henry. Harry and Basil are only ten years older than Dorian, so it seems strange to have them played by actors who are clearly older than him. My pick for Lord Henry was always David Tennant. He's younger, attractive, and roguish, and has those features that Oscar Wilde describes in the novel.

5. All of Dorian's indulgences are to do with sex. Ok, some of it is with drugs as well, and while it is heavily suggested in the novel that his exploits and exploitation of women are sexual in nature (and most likely with men, too), there is a hint that Dorian's relationship with other men involves other sins. Drug use is almost certainly one of them, but gambling to me seems another obvious sin he indulges in and allows others to lose themselves in. One of his former aquaintances goes bankrupt, and while paying for hookers and drugs all the time will help that along, so will gambling. And gambling was also frowned upon at the time. But in Dorian Gray, it's all an excuse to show sex scenes. Surely, sometimes it's more shocking to leave misdeeds to the imagination?

6. The film opens with Basil's murder. This suggests before we've even started that Dorian will become a horrible person. Which is ok, I guess. Hitchcock wouldn't mind it - suspense and all that. But then we get a flashback. A title appears on the screen: 'One Year Earlier'. What! No! Dorian kills Basil much later than that. And no one discovers Basil's body. Dorian makes absolutely sure of that, through blackmailing an old friend, Alan, into doing it for him. Alan is a minor character in the film, so he could have been called upon to do this. Instead, Dorian clumsily disposes of the body, it's found, and after Basil's funeral Dorian goes travelling for 25 years. When he returns, everybody is confused at his agelessness, and seem a little uncomfortable in his presence. But they quickly get over it. They get over it. People are surprised and jealous that Dorian never seems to age, which means they don't really question his strange appearance. Remove him from the picture, so to speak, and it seems shocking. But I get it, everything has to be so obvious in a film, right? So his actions have to have huge consequences...

7. ...Except that subtlety is Wilde's strongest point. The point of the novel is that Dorian's shallow decision ruins him, but it is a prison of his own making; he destroys himself, and other people and their superficial natures keep them from seeing his own. The comment is that society ignores the soul all the time. Dorian's morality, or lack thereof, is what has changed his life. There need be no outside punishment - internal punishment is enough. And this could have been done on film perfectly, hello, Crimes and Misdemeanors? The Player? And those films go further than The Picture of Dorian Gray. Their protagonists, rather than going mad at the lack of external punishment for their crimes, actually get over it. So the filmmakers could have been true to the book in this sense. They try, but it's too little too late. James is killed, but Dorian is only slightly haunted. So Harry then must deliver the punishment, by discovering Dorian's secret.

8. The homoerotic subtext from the book is clumsily handled. The novel begins with Basil nervously revealing to Harry that he may be revealing his love for Dorian in his paintings. He is afraid of these feelings, and needs Harry to help him understand them. Harry dismisses them, perhaps going on to have them for Dorian himself. In any case, there does appear to be a love triangle of sorts until Sybil's intrusion. The first film adaptation was made in 1945, in Hollywood, and so subject to the Hays Code. So, no homosexual subtext there. So, come the 2009 version, and no such strictures to be placed on the film, how is this handled? Terribly. Some creepy looks from Colin Firth, a quick glance at Dorian's naked back from Ben Chaplin's Basil, and...oh, a kiss and the suggestion of oral sex. Yep. That's it. Dorian comes on to Basil to distract him from the missing portrait. And it doesn't really work. In the novel, Basil's feelings are pretty obvious, and the film is all about being obvious. So why handle this theme so badly? It is very annoying. What would have been truer to the novel would have been Dorian drawing out a confession from Basil as a distraction, but also having Dorian slightly appalled by Basil. It seems obvious to most readers that Dorian and Harry have feelings for each other; they even live together at one point! Why not use more of that?

9. Harry has a daughter that makes him tame. This isn't so bad as it sounds, actually. In the novel, strong female characters are lacking. Wilde must have noticed this, because toward the end of the novel he introduces the little Duchess, Gladys. She's Harry's cousin, so they have verbal sparring matches and she seems able to see through Harry's nonsense. It's also clear that despite being married, she is taken with Dorian, who flirts with her but takes it no further. After the incident with James he is determined to change his life. I'm not this character is entirely necessary to the plot, but she is a strong female character designed to challenge Harry's sexist ideas. Making her Harry's daughter is interesting, but she's never quite as strong as Gladys is in the novel. I think she's also a nod to Dorian's country girl, whom he abandons as an act of what he thinks is contrition, and Harry thinks is self-serving. Again, I'm not sure it works, but I don't find it entirely offensive, either.

10. There is a ridiculous subplot involving Dorian's memories of abuse at the hands of Lord Kelso. It seems that the only purpose it serves is to show Dorian's imperfection and perhaps a more credible explanation for his propensity toward cruelty. This is handled differently in the novel, but it would have been hard to translate onto film. Dorian does a family history and finds that previous generations have indulged in sin and madness just as he does, and he wonders if he's simply inherited this behaviour and if the picture isn't just a figment of his imagination. But again, it is dealt with so swiftly in the film that it's clumsy. It seems little more than a visual device to reveal to Dorian that the picture is taking on all his imperfections. Which isn't strictly what the novel suggests.

11. The picture is a monstrous, living thing, seemingly infested with maggots. I can understand the film wanting to make the portrait more organic, but does it have to be so stupid? It's so loud that it's uncomfortable. And it seems to be able to see. In the film, we get subjective pov shots from the painting. I don't really like this. I like that the portrait remains largely unseen both in the novel and the 1945 film. When you do finally see it in the 1945 film it's truly hideous. I still find it disturbing. This is pretty much it:

Much scarier than the picture in Dorian Gray. The portrait should have been more like the shark in Jaws. Unseen and therefore more terrifying. And largely unheard.

It's not all bad, I guess. I did mention that Ben Barnes is ridiculously attractive? Ben Chaplin is pretty good as Basil. Colin Firth seems miscast. I like all of Rebecca Hall's appearances in film, so I enjoyed her turn as Emily Wootten. The costumes were pretty? Oh, I give up, I really hated it. I hated its guts. I vow to do Oscar justice!

Whenever I read The Picture of Dorian Gray, which is often, I am amazed at the way this study of morality is so timeless and remains relevant even today. I've secretly wanted to adapt this book properly (see previous blog entries for more), and I thought perhaps I'd lost my chance when I read in Interview that Benjamin Barnes was playing Dorian Gray. Yeah...still have a chance to do it right.

Because the novel is really about the soul. Does it exist? What if we could see the ways in which we corrupt our soul? Would we use it as a constant reminder to be morally good, or would we use it to be bear the burden of all our misdeeds? It's also about society's obssession with youth, and what we would forego to recapture our youth. As Harry says, the only way to recapture your youth is to remember all the mistakes you made, and make them over again.

Which, by the way, is one of the very few lines of dialogue from the novel that feature in the film. I cannot believe the extent to which this film ignores the themes and concerns of the novel. All references to morality, pleasure and the soul are skipped over, so insubstantial that you feel they were put in as a break from all the sex scenes.

There are changes to the novel that make the film's plot and story seem weak. Sybil Vane's dramatic appearances are nonexistent, and therefore so is the reason for her suicide. And any credible reason for Dorian's dismissal of her. Dorian and Lord Henry, or Harry, become very superficial characters, praising only art, and pursue beauty at all costs, Dorian more so than Harry. And yet the writer has ignored this for the most part. The conversation that leads to Dorian's wish that Basil's portrait of him age is almost entirely superficial, but for the wrong reasons. Sure, there are a lot of conversations in the novel that would be hard to translate into film, but the dialogue has been paraphrased to the point of meaninglessness.

In the plot, essentially, Dorian meets Basil, who paints a portrait of him. He meets Harry, who takes him to a seedy bar and tells him to drink up. Dorian decides this is a good idea and gives his soul for eternal youth. The portrait begins to age and bear all the scars of his sexual conquests. He kills Basil after showing him the portrait, then buggers off for 25 years. Harry has a daughter, who Dorian falls in love with, Harry discovers his secret and tries to kill him. Then Dorian decides to let himself be destroyed with the picture after Harry's daughter Emily tries to save him. Dorian destroyed, the portrait reverts back to its former glory. Harry keeps it.

It seems like the novel, but it's so disgustingly superficial. The characters, the visual style, the narrative, and that's what it should be! Because describing in detailed paragraphs why the film is such a poor adaptation would take way too long, I'm going to list them here:

1. Dorian is a brunette. In the novel, he looks young, barely 20, and angelic, with curly golden hair and bright blue eyes. He looks like an innocent babe, which makes his eternal youth seem like a blessing. It also saves him from being completely ostracised from society. When people see his young face and angelic looks, they can't believe the stories are true. Ben Barnes is gorgeous, don't get me wrong, but he always looks dangerous and saucy. You never believe in his innocence, even when he really is.

2. Sybil knows Dorian's name. She only ever knows his first name in the novel, and calls him Prine Charming. One of Dorian's former conquests knows this and refers to him so at the opium den, which leads James Vane to find him. In the novel, Dorian's engagement to Sybil is known only to Sybil and her family, Basil and Harry. Dorian fears his involvement with her death and Harry assures him that no one will ever know. Which makes it more shocking later when his past catches up with him in the form of James Vane trying to kill him.

3. Dorian's pleasure in art is absent. Which changes his relationship with Sybil, making it little more than a plot device. Dorian's treatment of her is truly cruel, the first time we see what he is capable of now his soul is separate from him, and Lord Henry's influence is almost total. His preference for art over some life is what makes both he and Harry more monstrous, and the breakdown of his and Sybil's relationship looks foolish, making her suicide foolish. Sybil is essentially an actress. All she knows is the theatre, and the only things she knows about romance she learned from Shakespeare. It is this investment in drama that attracts Dorian, and when she discovers reality, it repels him. So her final desperate act is her return to drama. It is diminished in the film, especially as it is Sybil who dismisses Dorian, not the other way around.

4. Harry seems intentionally malicious at points. Though Harry is shallow and cruel, his corruption of Dorian is never a serious attempt to ruin the boy. He sees a blank canvas. Just as Basil is inspired by Dorian's physical beauty, Harry is inspired by Dorian's naivety. He sees someone he can model after himself, someone not as bound to societal rules as he is, being married and held in high regard by his family. He's also bored with his society and with Basil. He's not as cruel as he seems in the first half of the film. I never thought Colin Firth would make a good Lord Henry. Harry and Basil are only ten years older than Dorian, so it seems strange to have them played by actors who are clearly older than him. My pick for Lord Henry was always David Tennant. He's younger, attractive, and roguish, and has those features that Oscar Wilde describes in the novel.

5. All of Dorian's indulgences are to do with sex. Ok, some of it is with drugs as well, and while it is heavily suggested in the novel that his exploits and exploitation of women are sexual in nature (and most likely with men, too), there is a hint that Dorian's relationship with other men involves other sins. Drug use is almost certainly one of them, but gambling to me seems another obvious sin he indulges in and allows others to lose themselves in. One of his former aquaintances goes bankrupt, and while paying for hookers and drugs all the time will help that along, so will gambling. And gambling was also frowned upon at the time. But in Dorian Gray, it's all an excuse to show sex scenes. Surely, sometimes it's more shocking to leave misdeeds to the imagination?

6. The film opens with Basil's murder. This suggests before we've even started that Dorian will become a horrible person. Which is ok, I guess. Hitchcock wouldn't mind it - suspense and all that. But then we get a flashback. A title appears on the screen: 'One Year Earlier'. What! No! Dorian kills Basil much later than that. And no one discovers Basil's body. Dorian makes absolutely sure of that, through blackmailing an old friend, Alan, into doing it for him. Alan is a minor character in the film, so he could have been called upon to do this. Instead, Dorian clumsily disposes of the body, it's found, and after Basil's funeral Dorian goes travelling for 25 years. When he returns, everybody is confused at his agelessness, and seem a little uncomfortable in his presence. But they quickly get over it. They get over it. People are surprised and jealous that Dorian never seems to age, which means they don't really question his strange appearance. Remove him from the picture, so to speak, and it seems shocking. But I get it, everything has to be so obvious in a film, right? So his actions have to have huge consequences...

7. ...Except that subtlety is Wilde's strongest point. The point of the novel is that Dorian's shallow decision ruins him, but it is a prison of his own making; he destroys himself, and other people and their superficial natures keep them from seeing his own. The comment is that society ignores the soul all the time. Dorian's morality, or lack thereof, is what has changed his life. There need be no outside punishment - internal punishment is enough. And this could have been done on film perfectly, hello, Crimes and Misdemeanors? The Player? And those films go further than The Picture of Dorian Gray. Their protagonists, rather than going mad at the lack of external punishment for their crimes, actually get over it. So the filmmakers could have been true to the book in this sense. They try, but it's too little too late. James is killed, but Dorian is only slightly haunted. So Harry then must deliver the punishment, by discovering Dorian's secret.

8. The homoerotic subtext from the book is clumsily handled. The novel begins with Basil nervously revealing to Harry that he may be revealing his love for Dorian in his paintings. He is afraid of these feelings, and needs Harry to help him understand them. Harry dismisses them, perhaps going on to have them for Dorian himself. In any case, there does appear to be a love triangle of sorts until Sybil's intrusion. The first film adaptation was made in 1945, in Hollywood, and so subject to the Hays Code. So, no homosexual subtext there. So, come the 2009 version, and no such strictures to be placed on the film, how is this handled? Terribly. Some creepy looks from Colin Firth, a quick glance at Dorian's naked back from Ben Chaplin's Basil, and...oh, a kiss and the suggestion of oral sex. Yep. That's it. Dorian comes on to Basil to distract him from the missing portrait. And it doesn't really work. In the novel, Basil's feelings are pretty obvious, and the film is all about being obvious. So why handle this theme so badly? It is very annoying. What would have been truer to the novel would have been Dorian drawing out a confession from Basil as a distraction, but also having Dorian slightly appalled by Basil. It seems obvious to most readers that Dorian and Harry have feelings for each other; they even live together at one point! Why not use more of that?

9. Harry has a daughter that makes him tame. This isn't so bad as it sounds, actually. In the novel, strong female characters are lacking. Wilde must have noticed this, because toward the end of the novel he introduces the little Duchess, Gladys. She's Harry's cousin, so they have verbal sparring matches and she seems able to see through Harry's nonsense. It's also clear that despite being married, she is taken with Dorian, who flirts with her but takes it no further. After the incident with James he is determined to change his life. I'm not this character is entirely necessary to the plot, but she is a strong female character designed to challenge Harry's sexist ideas. Making her Harry's daughter is interesting, but she's never quite as strong as Gladys is in the novel. I think she's also a nod to Dorian's country girl, whom he abandons as an act of what he thinks is contrition, and Harry thinks is self-serving. Again, I'm not sure it works, but I don't find it entirely offensive, either.

10. There is a ridiculous subplot involving Dorian's memories of abuse at the hands of Lord Kelso. It seems that the only purpose it serves is to show Dorian's imperfection and perhaps a more credible explanation for his propensity toward cruelty. This is handled differently in the novel, but it would have been hard to translate onto film. Dorian does a family history and finds that previous generations have indulged in sin and madness just as he does, and he wonders if he's simply inherited this behaviour and if the picture isn't just a figment of his imagination. But again, it is dealt with so swiftly in the film that it's clumsy. It seems little more than a visual device to reveal to Dorian that the picture is taking on all his imperfections. Which isn't strictly what the novel suggests.

11. The picture is a monstrous, living thing, seemingly infested with maggots. I can understand the film wanting to make the portrait more organic, but does it have to be so stupid? It's so loud that it's uncomfortable. And it seems to be able to see. In the film, we get subjective pov shots from the painting. I don't really like this. I like that the portrait remains largely unseen both in the novel and the 1945 film. When you do finally see it in the 1945 film it's truly hideous. I still find it disturbing. This is pretty much it:

Much scarier than the picture in Dorian Gray. The portrait should have been more like the shark in Jaws. Unseen and therefore more terrifying. And largely unheard.

It's not all bad, I guess. I did mention that Ben Barnes is ridiculously attractive? Ben Chaplin is pretty good as Basil. Colin Firth seems miscast. I like all of Rebecca Hall's appearances in film, so I enjoyed her turn as Emily Wootten. The costumes were pretty? Oh, I give up, I really hated it. I hated its guts. I vow to do Oscar justice!

Thursday, September 24, 2009

Radio, live transmission

I was watching a behind-the-scenes special on the ole tube of You about Flight of the Conchords the other day, because yes, that's what you do when you're the wrong side of 25 in Manchester during Freshers Week. And I noticed something very interesting. Well, other than that Bret and Jemaine are stone cold foxes. I've been noticing that for years.

When they were talking about the television programme's genesis, they forgot to mention something quite important; that they made a BBC radio series similar in style and content to the television series.

In this way their rise to mainstream success of sorts is similar to that of the Mighty Boosh. Both started as a comedy act, then went on to make a radio series, which then lead to a television programme. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Not many are familiar with either radio series, and I think it's a shame. I've made a radio play and I've done some stuff in radio as part of my studies, and you begin to fall out of love with the visual image when you have aural storytelling. As someone who adores the image and filters her entire life through a screen, it sounds weird saying that sometimes I prefer a good old radio play. If it's done well, that is.

With any piece of art you rely on the spectator to interpret the information and literally piece it together to understand. When you watch a film you're essentially making sense of thousands of still images and creating a meaningful narrative.

And even with a book, you don't have images in front of you to make sense of to create a narrative, you have words that you piece together to create an image in your mind (and it's always better than the one filmmakers give you, right?). But listening to a radio play or a soundscape is different, because when you listen to a soundscape, when you're engaging with it, you think you're hearing familiar sounds when you're probably not.

For example, the soundscape or production I made was a radio show being interrupted by a zombie attack. The sound of people bashing zombie brains in was actually us throwing a watermelon against a brick wall. The sound of girlish screams was actually my male friend sucking in his breath and making weird screeches.

That's why everyone is rubbish at Secret Sound - it could be any bloody thing! It could be bread popping out of a toaster, but it could sound like something completely different. It's like asking someone to be a sound designer or a foley artist in order to win at that thing.

But I digress. There was this dude, a dude, named Lev Kuleshov. And he devised a series of experiments designed to show that audiences can interpret images simply by the way they are connected to another image. In one of his experiments, he used the same medium close-up of a man and connected it with different images. The idea was that people would make assumptions about the man's state of mind based on whatever the next image was. So if the man's face was followed by a bowl of soup, a spectator would say that he was hungry. And if it was followed by a shot of a child, the man loved the child.

Now, I hear these experiments didn't really work, but it's an interesting idea. Kuleshov must have been pretty important, because he also has an effect named after him; the Kuleshov Effect (cool, right?). Essentially, the Kuleshov effect is when the filmmaker manipulates spatial relations in a particular way. Usually, the filmmaker infers a space with the use of limited shots; two or three, and no establishing shot. Classical Hollywood cinema and its continuity system would have you believe that in order for an audience to understand spatial relations, each new shot had to have an establishing shot before going in for closer shots of the space and the characters within it. Kuleshov's experiments and such reveal that the audience really doesn't need that much visual information in order to do this. The easiest example I can give you is when a television show or film changes location from an exterior location to an interior location (Friends: ext shot of Monica's building, then int shot of her apartment). Kuleshov's affecting us all over the shop, basically.

And the Kuleshov Effect works so well in radio, too. The spectator imagines a space based entirely on what they hear. If you can hear dripping water, an characters' dialogue has an echo, you probably think they're in a cave, right? Or, you hear the sounds of birds and trees and such, you assume you're in a forest.

And sometimes, you forget that humans, deep down, kind love the sound of their fellow mammals' voice. I have a friend who finds Noel Fielding's voice very soothing. For her, The Mighty Boosh radio series is both relaxing, and hilarious. What a lovely review.

There's something so irresistable about creating a space or a world relying only on one sense. In a lot of interviews, Julian Barratt seems to prefer creating soundscapes to that of the a visual space. I find it really enjoyable, even though I haven't done it in a while. And there's also the fact that I really know nothing about sound and sound production. All I know is, I can record sounds, shove them onto a track or many tracks on Protools and make them sound cool. I was recently asked to do sound design on a student project and I was a little scared...but then again, it could be really fun. Provided this uni I'm at has Protools, I guess.

But if you get nothing out of this post, do try and track down the Mighty Boosh radio series and the Flight of the Conchords radio series. You will not be disappointed.

When they were talking about the television programme's genesis, they forgot to mention something quite important; that they made a BBC radio series similar in style and content to the television series.

In this way their rise to mainstream success of sorts is similar to that of the Mighty Boosh. Both started as a comedy act, then went on to make a radio series, which then lead to a television programme. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Not many are familiar with either radio series, and I think it's a shame. I've made a radio play and I've done some stuff in radio as part of my studies, and you begin to fall out of love with the visual image when you have aural storytelling. As someone who adores the image and filters her entire life through a screen, it sounds weird saying that sometimes I prefer a good old radio play. If it's done well, that is.

With any piece of art you rely on the spectator to interpret the information and literally piece it together to understand. When you watch a film you're essentially making sense of thousands of still images and creating a meaningful narrative.

And even with a book, you don't have images in front of you to make sense of to create a narrative, you have words that you piece together to create an image in your mind (and it's always better than the one filmmakers give you, right?). But listening to a radio play or a soundscape is different, because when you listen to a soundscape, when you're engaging with it, you think you're hearing familiar sounds when you're probably not.

For example, the soundscape or production I made was a radio show being interrupted by a zombie attack. The sound of people bashing zombie brains in was actually us throwing a watermelon against a brick wall. The sound of girlish screams was actually my male friend sucking in his breath and making weird screeches.

That's why everyone is rubbish at Secret Sound - it could be any bloody thing! It could be bread popping out of a toaster, but it could sound like something completely different. It's like asking someone to be a sound designer or a foley artist in order to win at that thing.

But I digress. There was this dude, a dude, named Lev Kuleshov. And he devised a series of experiments designed to show that audiences can interpret images simply by the way they are connected to another image. In one of his experiments, he used the same medium close-up of a man and connected it with different images. The idea was that people would make assumptions about the man's state of mind based on whatever the next image was. So if the man's face was followed by a bowl of soup, a spectator would say that he was hungry. And if it was followed by a shot of a child, the man loved the child.

Now, I hear these experiments didn't really work, but it's an interesting idea. Kuleshov must have been pretty important, because he also has an effect named after him; the Kuleshov Effect (cool, right?). Essentially, the Kuleshov effect is when the filmmaker manipulates spatial relations in a particular way. Usually, the filmmaker infers a space with the use of limited shots; two or three, and no establishing shot. Classical Hollywood cinema and its continuity system would have you believe that in order for an audience to understand spatial relations, each new shot had to have an establishing shot before going in for closer shots of the space and the characters within it. Kuleshov's experiments and such reveal that the audience really doesn't need that much visual information in order to do this. The easiest example I can give you is when a television show or film changes location from an exterior location to an interior location (Friends: ext shot of Monica's building, then int shot of her apartment). Kuleshov's affecting us all over the shop, basically.

And the Kuleshov Effect works so well in radio, too. The spectator imagines a space based entirely on what they hear. If you can hear dripping water, an characters' dialogue has an echo, you probably think they're in a cave, right? Or, you hear the sounds of birds and trees and such, you assume you're in a forest.

And sometimes, you forget that humans, deep down, kind love the sound of their fellow mammals' voice. I have a friend who finds Noel Fielding's voice very soothing. For her, The Mighty Boosh radio series is both relaxing, and hilarious. What a lovely review.

There's something so irresistable about creating a space or a world relying only on one sense. In a lot of interviews, Julian Barratt seems to prefer creating soundscapes to that of the a visual space. I find it really enjoyable, even though I haven't done it in a while. And there's also the fact that I really know nothing about sound and sound production. All I know is, I can record sounds, shove them onto a track or many tracks on Protools and make them sound cool. I was recently asked to do sound design on a student project and I was a little scared...but then again, it could be really fun. Provided this uni I'm at has Protools, I guess.

But if you get nothing out of this post, do try and track down the Mighty Boosh radio series and the Flight of the Conchords radio series. You will not be disappointed.

Labels:

bbc,

flight of the conchords,

kuleshov,

radio,

rob brydon,

soundscape,

the mighty boosh

Saturday, September 19, 2009

The Dream

Every year I watch the Academy Awards on television I wonder what it would be like to win. I fantasise about what I would wear, how I would have my hair and what shoes would go with my dress.

I think about what I say in my speech and the award I might possibly win (Best Director, Best Original Screenplay or Best Picture? Sky's the limit).

However, the biggest fantasy is the afterparty. At this imaginary celebration of winners, I interrupt my conversation with some young Hollywood hottie when I spy Martin Scorsese, clutching yet another Oscar (now he's won one, they're sure to follow). Here is how the conversation goes:

Me: Excuse me, Sir, but I would just like to say that you are an amazing filmmaker and that as a film critic before a filmmaker, you've really inspired.

Marty: Well, thank you. You know, I saw your film and I have to say, it's incredible.

Me (blushing): Oh, thank you, Mr Scorsese, that's so nice of you!

Marty: Every year I'm impressed with the young kids coming through.

Me: Well, Mr Scorsese, I think that your films are such a complex analysis of masculinity and violence. Going from Mean Streets to the Departed, you can see the ways in which the two concepts are so intertwined.

And on I go, demonstrating the ways in which, if you analyse his films chronologically you can see that a lot of the same cycles of vengeance are repeated, and does he think that men haven't really found a way to break out of these patterns of behaviour, and he answers at length. In my fantasy, I do a lot of the talking. But Marty loves it - he tells me to call him Marty and it's incredible.

So scoff if you will at my humble little dream, but I bet all of you have a secret little inner nerd, dying to have an imaginary conversation with a great like Scorsese.

Now, Tarantino and I - that could be a long one.

I think about what I say in my speech and the award I might possibly win (Best Director, Best Original Screenplay or Best Picture? Sky's the limit).

However, the biggest fantasy is the afterparty. At this imaginary celebration of winners, I interrupt my conversation with some young Hollywood hottie when I spy Martin Scorsese, clutching yet another Oscar (now he's won one, they're sure to follow). Here is how the conversation goes:

Me: Excuse me, Sir, but I would just like to say that you are an amazing filmmaker and that as a film critic before a filmmaker, you've really inspired.

Marty: Well, thank you. You know, I saw your film and I have to say, it's incredible.

Me (blushing): Oh, thank you, Mr Scorsese, that's so nice of you!

Marty: Every year I'm impressed with the young kids coming through.

Me: Well, Mr Scorsese, I think that your films are such a complex analysis of masculinity and violence. Going from Mean Streets to the Departed, you can see the ways in which the two concepts are so intertwined.

And on I go, demonstrating the ways in which, if you analyse his films chronologically you can see that a lot of the same cycles of vengeance are repeated, and does he think that men haven't really found a way to break out of these patterns of behaviour, and he answers at length. In my fantasy, I do a lot of the talking. But Marty loves it - he tells me to call him Marty and it's incredible.

So scoff if you will at my humble little dream, but I bet all of you have a secret little inner nerd, dying to have an imaginary conversation with a great like Scorsese.

Now, Tarantino and I - that could be a long one.

Sunday, August 16, 2009

Did I help kill the Supermodel?

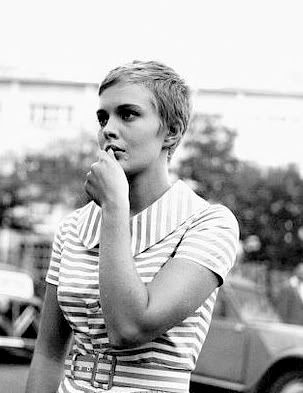

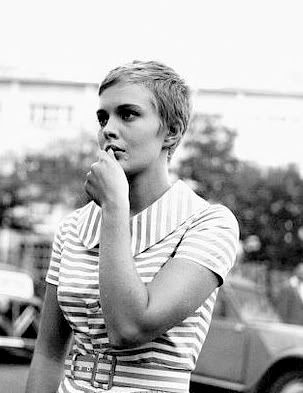

When I think about the people who influence my personal style, or I see the latest trends in magazines, I realise that I'm not inspired by designers or models (Kate Moss and Twiggy excepted).

I'm more often inspired by moments in film, or musicians or actors. So, in preparation for my inevitable fame, I thought I would tackle the question, what are your style influences?

You're inspired by Kirsten Dunst wearing a blanket? That's probably what you're thinking. No. Look at the cuff/bracelet on her right wrist. I searched for one exactly like it for four years and finally found a couple of months ago at Diva for ten clams (that's dollars for those of you playing at home).

I am inspired by Kirsten Dunst, too. I don't care what Perez Hilton says about her, I think she does effortless style so well. I've sort of had a girl crush on her since Dick (how ironic!) and I'm a fan of everything she does.

It's a shame that I could only find this picture in black and white, because it was Sissy's copper locks and beautiful naivete in Badlands that makes me want to wear blue jeans and ruffle shirts every day, and you need to see it through the dusty palette of Terence Malick's visual style. And Martin Sheen in that film? Devine...needless to say, it was Sissy who cemented my decision to go back my natural hair colour. Thanks, man.

"You can have anything you want in life if you dress for it."

Edith Head's words of wisdom are echoed in modern fashion editorials, makeover shows and the phrase "dress for the job you want, not the job you have." If I took this too literally I would walk around in a flat cap, puffy plaid directing pants and a kerchief. And my chief accessory would be one of those old-fashioned megaphones. But I'll just have to content myself with black shirt-dresses, tights ankle boots and a blazer. Sigh.

But Edith Head is a huge influence for more than this: she is responsible for the most memorable looks from Alfred Hitchcock's best films. And her signature style (round sunglasses, suits, blunt fringe) could be easily adapted for today.

My favourite Edith Head look? Oh so many, but I think the one that stands out for me is the grey suit Kim Novak wears in Vertigo:

That whole film is amazing, but the way in which Head uses clothing to evoke character is phenomenal. Patricia Field comes close to this in the modern age, I think, but no one can touch Edith Head when it comes to putting together an immaculate suit.

When you first see Patricia Franchini sashaying down the street in her New York Herald Tribune t-shirt, cigarette pants and ballet flats and maybe you're not sure why she's charmed our smooth criminal Michel Poiccard. But I know; she's so cool, calm and indifferent, and manages to look absolutely gorgeous in androgynous clothes and short hair.

When she leaves Michel, she is in a full skirt and her transition from love interest to femme fatale is complete. Every time I see her rub her top lip I want to cut off all my hair and break hearts just to see if I can (I'd look rubbish with hair that short, though. Sigh).

I could sum up why Noel Fielding is so attractive in three little words: Joan Jett Jumpsuit. But you might not know what I mean. Why is he on a list of my influences? Because his appeal for me is twofold; I want to be with him and I want my hair like his. One day I'll bring this picture in to my hair dresser and ask for "your basic backcomb structure, slightly root-boosted and framed in a cheeky fringe." Aaaah.

Long before Lady Gaga was stepping out in control briefs and a blazer, Edie Sedgwick made going out sans pantalons look adorable. I have a t-shirt long enough to wear as a dress and the urge to just wear it with my black ribbed tights was so strong. But then I spent most of the day pulling it down self-consciously around the house and thought, sorry Edie, I just don't have the body or confidence for it. But I do have the laziness for it. Which is a good start. And in the meantime, I'll wear my blazer with control briefs AND tights, thanks, Lady Gaga.

XX